Modernisation has majorly changed the quintessence of tattooing; for some of us it’s purely artistic, for others it’s an individual project, a mark of a more stylish urban uniqueness perhaps different to a cultural one. But if you dig deeper into the custom, you’ll find that in most parts of the world, tattooing is a practice that holds innumerable forms of insinuation depending on where you lived and what era you lived in.

In India too, the art of tattooing has existed for hundreds of years, and thousands of people – almost solely tribal people as far as history goes – have had ink enduringly mark their skin for various reasons.

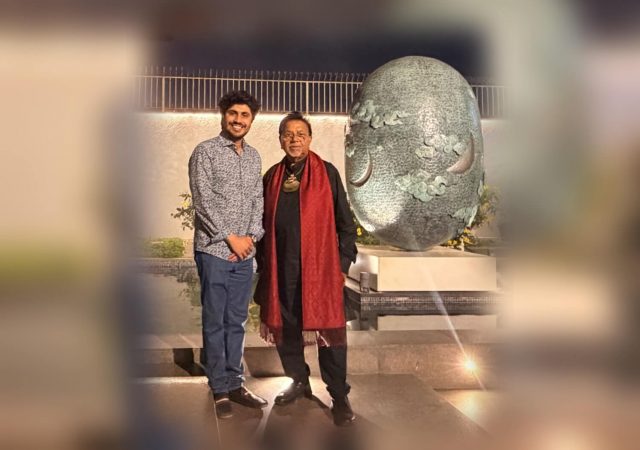

For 21-year-old Heleena Mistry, tattoos are a part of her Indian identity as a young Gujarati kid born and raised in Leicester, UK. She was 18 years old when she decided to get into the tattoo industry – ‘My mum gave me her blessing and I just went for it.’ Seeing a lack of South Asian female tattoo artists, she wanted to fill that gap in the market.

Indian families are nothing if critical when it comes to the young ones’ choosing career paths and life choices. From raised eyebrows and pursed lips to those often snobbish clicks of the tongue. ‘I’m lucky enough to have easygoing parents, for a while they didn’t appreciate why I wanted to be a tattoo artist, and they gently tried to cheer me to get a regular 9-5 job, this was during periods where I was looking for tattoo studios to work in. My family as a whole usually kept their opinions to themselves but their facial expressions and tongue-tied remarks would say it all. That’s all stopped now since I’ve come a long way and owns my own studio now,’ says Mistry.

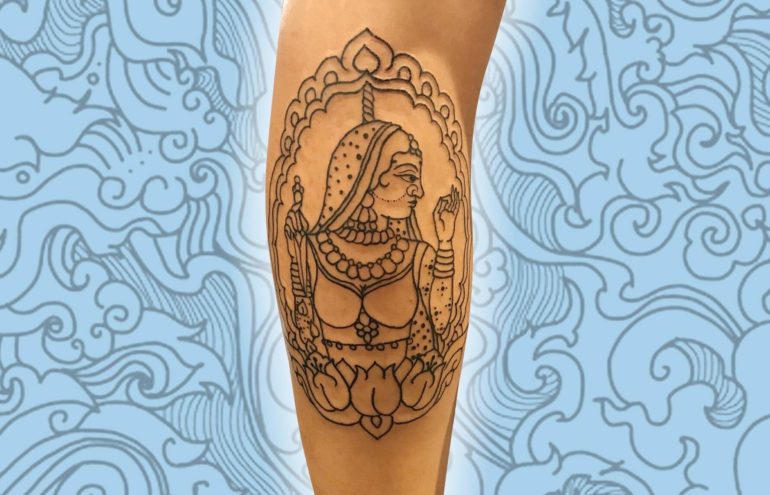

Her first tattoo, she shares, was a little umbrella that she did on her ankle when she was 19. ‘I was a trainee at the time and I had a tutor guiding me. Mistry’s has grown to have a very diverse style and art that is easy to identify on someone’s skin. Her designs draw motivation from Mughal miniatures, Hindu iconography and flower-patterned patterns, strong bold lines, stylistically Indian figures and motifs.

‘I just draw things inspired by the images we had in my home rising up. Most of the figures were drawn with a side profile; their bodies would be slightly out of share with high breasts and large eyes. When I first wanted to get into tattooing, I used to draw westernized pieces to fit into the industry, but I now know that it’s being true to myself and heritage that has allowed to express myself through my work,’ she said. ‘I definitely think the younger generation is appreciating traditional South Asian tattoos more openly. Growing up, most of us rejected our cultures to fit in with society, and now there’s a wave of people trying to reconnect with their culture and some people achieve that through getting traditional South Asian tattoos,’ she added further.

It hasn’t been easy, being a young woman of colour trying to steer through an industry that has for a long time been a space that was largely subjugated by men. Mistry faced her fair share of apprehensions and rejection from countless studios. Heleena has become someone many brown kids look up to, for pushing back, for powering through and figuring a space for her with pure talent and skill.

She never expected to turn into an inspiration for others just for chasing her own dreams, said, ‘All I’ve ever wanted was to be imaginative and have my dream job. I’m lucky enough to have gotten somewhere with my dreams, it means so much to me that I can be that example for others to go against the norm and work hard for something you really want! I don’t think it’ll ever sink in that by me chasing my dreams the younger generations have also found a confidence to do the same.’