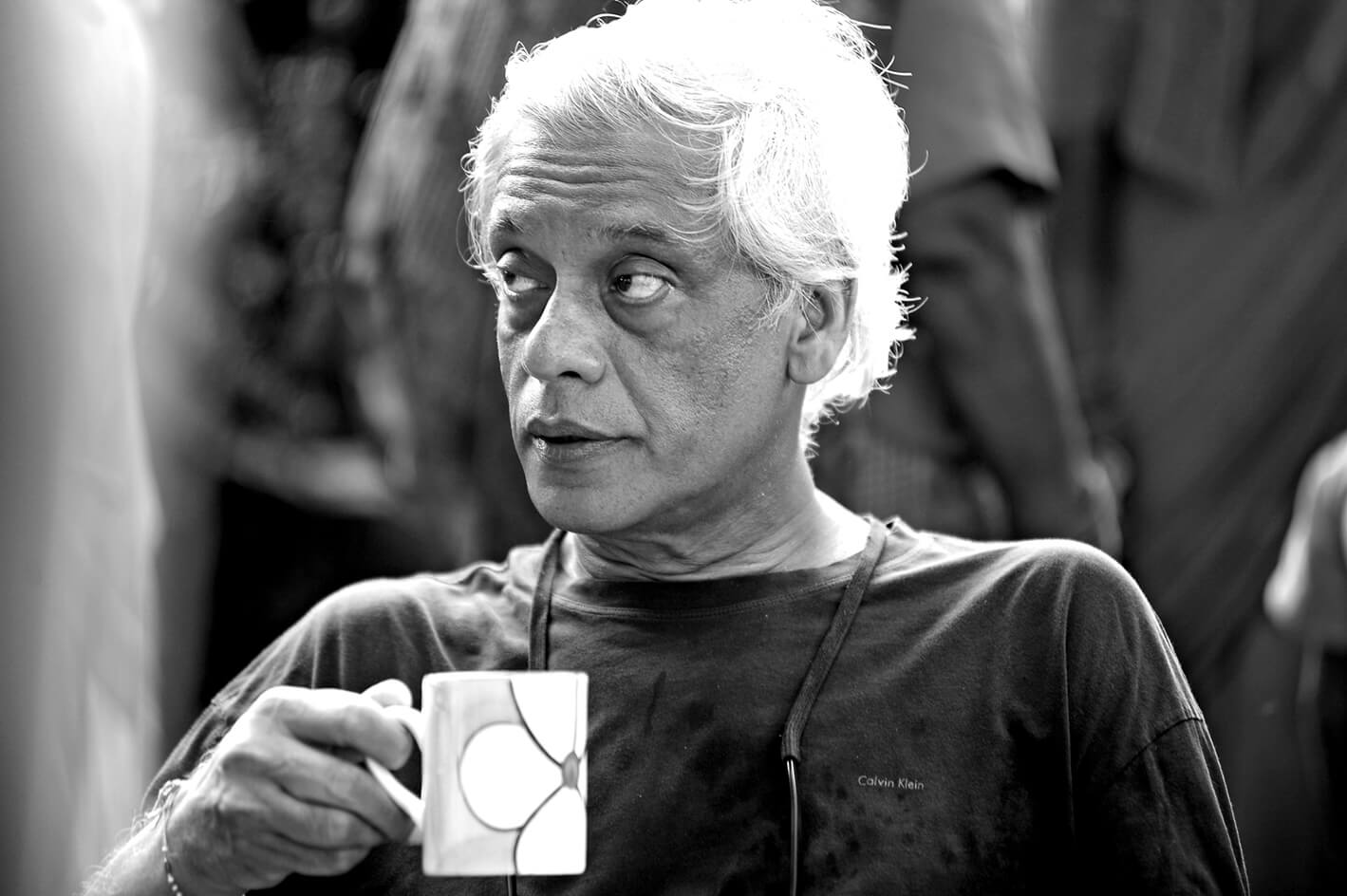

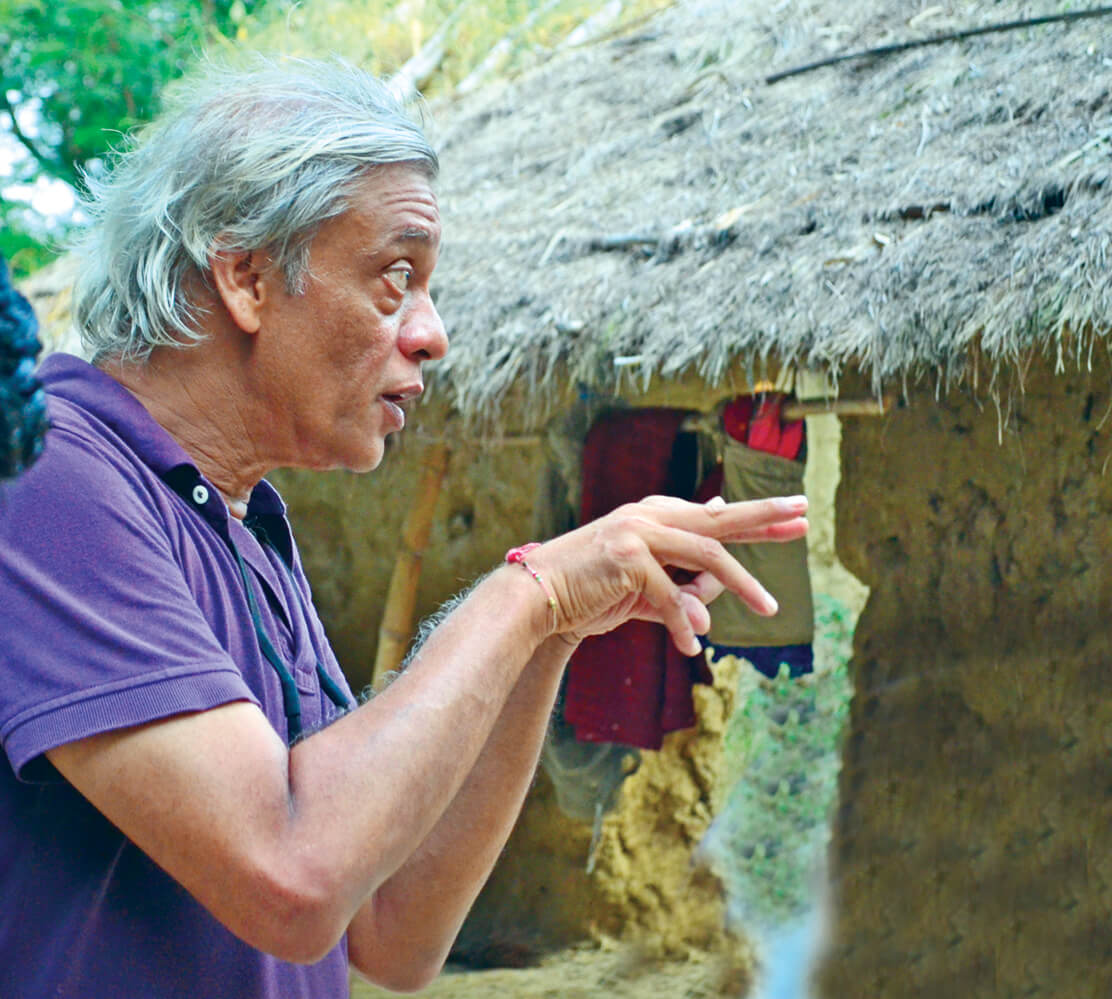

When I speak to Sudhir Mishra, he is in the throes of receiving a verdict for his latest film, curiously titled, Daas Dev. Here, Sudhir has made a conspiracy thriller out of the famous and probably the most recreated tome, Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay’s Devdas. The story is a potent mixture of love, politics, betrayal and mad ambition—an alchemy that has rarely failed. It has Sarat Chandra’s melancholy and brooding but the film is set in a Shakespearean atmosphere rather than a “Devdasian” one. Sudhir sensed a similarity between Devdas’ sense of uncertainty with that of Hamlet, hence the merger. “It has a love story at the centre, so it is about whether love is possible in times of lust and addiction to power,” he explains.

Just a few days prior to a film’s release can be quite tiring for a filmmaker. And, Sudhir Mishra is no exception. More so, considering success has eluded him in his last few outings. He admits to being nervous, but a show of his films to some good friends, whom he is sure, will give him a truthful opinion, has allayed his fears to an extent. “I showed the film to Ketan Mehta, Shekhar Kapur, Anurag Kashyap and a few others,” he says, sounding relieved. Shekhar said this was his best film as a director so far—that it was his best shot film. So, that has made Sudhir restore his faith in his skill as a filmmaker. I felt happy that my skill set was still in place,” he gushes. The rest, he knows, is up to the audience. He recalls an incident which further reinstates his confidence in his craft. “Javed saab (Akhtar) had asked me to watch Farhan’s first film and see if he knew his job or not. I said he was damn good. To that, he said,‘ Now, I am not worried about him. As long as he knows his work, whether this one works or not, someday he will make a successful film.’” Sudhir believes in this dictum.“If one’s talent is in place and one is doing what one is meant for, it is fine,” he convinces himself. Sudhir is happy with his creation and has a good feeling about it. Unlike when he made Calcutta Mail—he wasn’t too thrilled with what he saw. This time, however, he is proud.

The art of filmmaking has gone through great changes, and Sudhir, who calls himself the last well-known parallel filmmaker, says it is easier now for independent filmmakers and unique and sensitive storytellers like him. “I feel less lonely now, and I think that with directors like Anurag Kashyap, Vishal Bharadwaj, Vikram Motwane, Imtiaz Ali, Raju Hirani and Zoya Akhtar—the industry is a much more easy, non-confrontational place now. We are not fighting amongst ourselves. There is no battle line drawn between parallel and mainstream cinema,” says Sudhir, who has worked as an assistant to greats like Kundan Shah on the historic Jane Bhi Do Yaaron, apart from some celebrated auteurs like Ketan Mehta, Shekhar Kapur and Vidhu Vinod Chopra. Needless to say, they have had a tremendous influence on Sudhir as a person and have moulded his filmmaking sensibilities to what it is today to a large extent. “They were such generous, giving people,” remembers Sudhir and dubs them his ‘mad mentors’. Mad in the right way, and they still are, he insists. “They can get up any day and make a great film. They are still young in their heads,” he says respectfully.

For an individualistic filmmaker like Sudhir, the path can be more difficult as compared to those who are formulaic. Formula filmmakers always have an easier ride, feels Sudhir and adds that it has always been the case. “The ’50s to the early ’70s saw some great cinema, then it went downhill and now it’s back to all kinds of cinema. People now have more independence and voice to make films of their choice,” says Sudhir thoughtfully in his famous baritone.

Being around younger people making such great cinema is like a morale booster and an inspiration for the experimentative Sudhir, who admits he had lost his way a few years ago. But now, he is back and knows what he wants to make. “The student has to become the teacher,” he says, without any compunctions.

The credit goes to him too for keeping himself relevant, adapting to the changes and not being stuck to some nostalgic past—by looking forward and being brave enough to tell a story in an uninhibited and frank way.

Sudhir’s critically acclaimed film, Hazaron Khwahishen Aisi, is etched in the minds of those who have watched it. It has a universal appeal and must be Sudhir’s own benchmark to be surpassed. He doesn’t want to go there though. “You have to keep making new films,” he says plainly. However, a sequel to it is in the works. Another film he is working on is based on his late wife, film editor, Renu Saluja. It’s not a biopic in the true sense, but deals with the later phase of her life, probably after she was diagnosed with cancer and how it altered his life. “The script is in its third or fourth draft. It is a difficult one to do. One has to be very sensitive while handling it. It has to be made with a lot of care. I am not going to hurry it up,” says Sudhir.

Author and journalist Manu Joseph’s brilliant book, Serious Men, will be adapted by Sudhir soon. He is thrilled that Manu, who was one of the people whom Sudhir showed Daas Dev to, loved it. It meant a lot to him, considering Manu is not known to mince words.

It can’t be easy for a filmmaker to deal with the industry riddled with fickle people and selective memories. You just have to keep making films, says Sudhir for an answer. As for him, he keeps his sanity by maintaining connections outside the industry, retaining old friendships, and not getting carried away by fame. “Also, by understanding that you don’t write the film, but the story writes you,” he says, adding that one has to be faithful to the medium and be loyal to it.“Otherwise, she will walk away from you. You have to remember why you are here—you are here to make cinema, you love cinema and it loved you back. You have to keep retaining that relationship. It is such a beautiful medium, it makes better people out of all of us,” he pontificates.

Of course, he doesn’t rule out the fact that there are some people in the industry who are fickle and fake, frauds, who come in the garb of being very sensitive. Sudhir says one will be surprised how many frauds exist in the so-called earnest/sincere clothing. “I prefer the open bastards to these frauds,” he laughs. Well, we do too.