Google celebrated the 107th birthday of a groundbreaking Indian writer whose work was celebrated but equally censored for its honest depictions of women’s lives. Back in the 1930s, Ismat Chughtai wrote on female sexuality and femininity, middle-class gentility and class conflict – subjects considered taboo for the age. Born in a small town called Badayun, Uttar Pradesh, to a middle-class Muslim family in 1911, she was the ninth child among 10. Her father was a civil servant his postings made the family move around in various other places in India quite frequently.

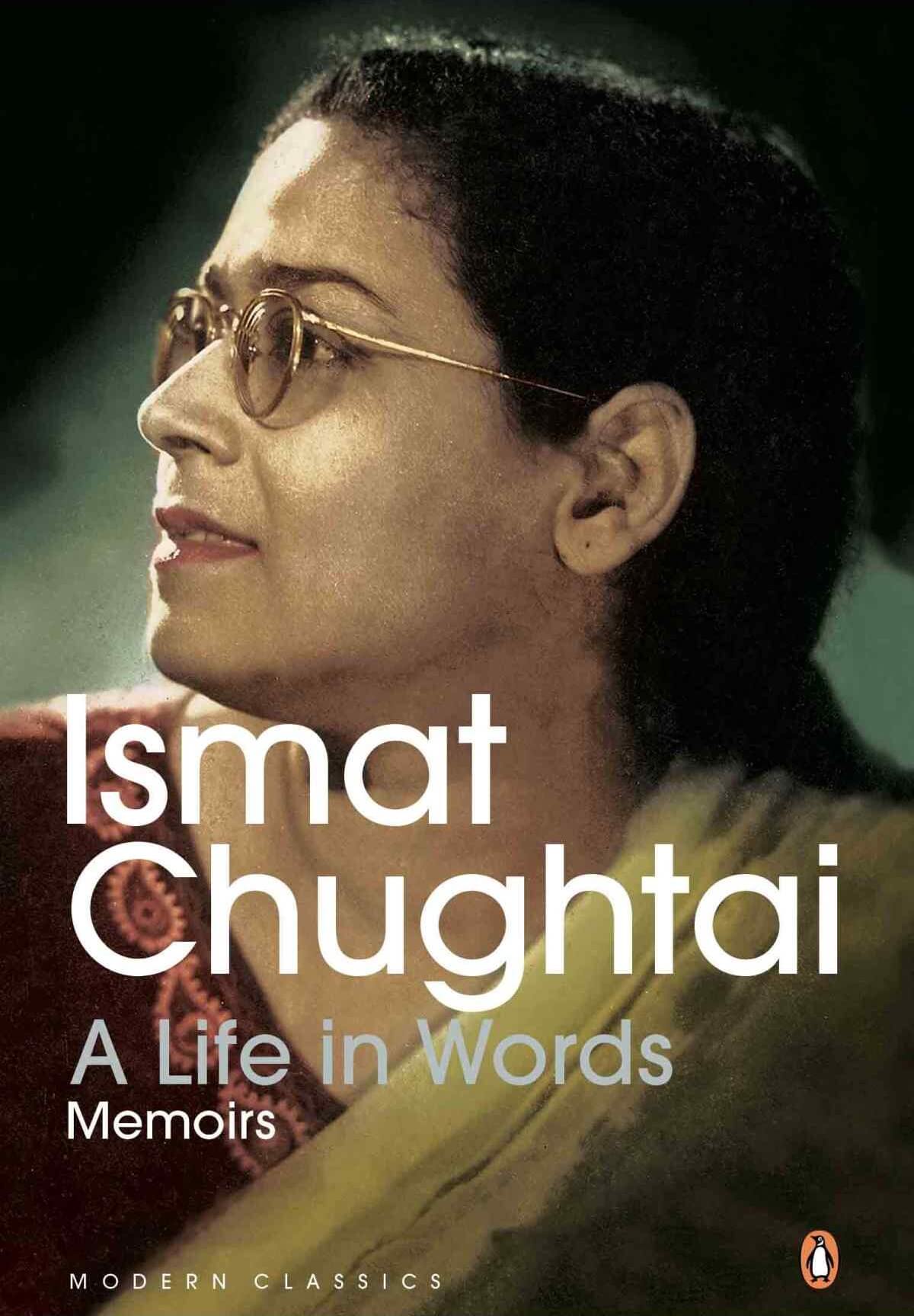

She was never interested in the knitting, stitching and homemaking skills which girls were taught at a young age back then, but what truly distinguished Ms Chughtai, however, was her desire for an education. She narrowly avoided an arranged marriage at the age of 15, after which she convinced her parents to let her pursue a bachelor’s degree at Isabella Thoburn College. She later studied teaching at Aligarh Muslim University and became the first Indian Muslim woman to obtain both a Bachelor of Arts and a Bachelor’s in Education degrees.

One of Chughtai’s older brothers — Mirza Azeem Beg — was a novelist; he and the Progressive Writers’ Association (a group that Chughtai encountered while pursuing a BEd at Aligarh Muslim University) influenced her decision to become a writer.

It is hard to forget the name Ismat Chugati as it stirred big controversies and made it to the news in the year 1942 for her work Lihaaf (the quilt). It was a tale about a neglected Begum who strikes up a romantic relationship with her masseuse, this ended up causing a great furore as it depicted female sexuality and their desires. She also withstood pressure from several senior Urdu writers (men, mostly) who advised her to apologise to the judge and have her case dismissed. Chughtai knew she had done no wrong, and refused to do so, she said she believed her lawyer would win her case.

To the judge who later told her that he didn’t find anything obscene in Lihaaf, but that Manto’s writings, who was also on a trial at the same time as her for his work Bu (Odour), were ‘littered with filth’, Chughtai responded, ‘The world is also littered with filth’. To which the judge questioned, ‘Is it necessary to rake it up, then?’ to which she confidently replied, ‘If it is raked up, it becomes visible and (then) people feel the need to clean it up.’

‘I am still labelled as the writer of Lihaaf. The story brought me so much notoriety that I got sick of life. It became the proverbial stick to beat me with and whatever I wrote afterwards got crushed under its weight,’ Ismat Chughtai wrote in an angered and disappointed tone in her memoir, A Life in Words. But if only she knew back then that her bold work is going to be an inspiration for the coming generations of writers and artists.

Left alone by her husband, Chughtai’s protagonist Begum Jaan takes charge of her life and navigates her way through the bindings of the patriarchal setup to express her sexual urges and satiate them. But Chughtai places the lihaaf, a quilt, of vagueness and euphemism over her writing as she explores the homoerotic theme in her story. Nothing is ever said aloud and the ploy of using a child narrator and borrowing her lexicon to recount the story serves Chughtai’s purpose well. The story, over the years, has emerged as a fitting example of the triumph of feminism and Begum Jaan is often viewed as the champion of it. The film adaptation of this masterpiece is set to release this year.

Ms Chughtai also dabbled in film, after marrying director and screenwriter Shahid Lateef. She wrote the screenplay for the 1948 Dev Anand film Ziddi (it was based on one of her short stories), and for the 1950 Dilip Kumar-starrer Arzoo. She also directed Faraib (1953) and co-wrote and produced Nutan’s Sone Ki Chidiya (1958).

Chughtai’s daughter, nephew and niece were married to Hindus. In her own words, Chugtai came from a family of ‘Hindus, Muslims and Christians who all live peacefully’. She was known to be an avid reader of not only Qur’an but also the Gita and the Bible.

Known to be the rebel till the end, some of her other enriched Urdu literature includes Til (The Mole), Tedhi Lakeer (The Crooked Line), Gharwali (The Homemaker), Gainda (The Marigold) all of which extensively talked, in her stories, about the women, their plights and their desires in a most beautiful manner.

Ms Chughtai was awarded the prestigious Padma Shree by the Indian government in 1976 for her contributions to the field of literature. She continued to have a prolific career, right until the 1980s when she was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s. Chughtai passed away in October 1991.